Traditional Portuguese Building Over Time

A brief overview into Portuguese building heritage over the centuries and how it was shaped by the many cultures that inhabited the Iberian peninsula.

SUSTAINABLE CONSTRUCTIONTRADITIONAL BUILDING

Mário Mateus

7/29/20259 min ler

Layers Upon Layers of Heritage

Traditional Portuguese architecture reflects a long and practical relationship between people, landscape, and natural resources. Across centuries, communities in Portugal built using what the land provided, shaping construction methods around local climate, geography, and collective ways of living.

Rather than being shaped by formal theory or imposed styles, these building traditions grew from direct observation, local experimentation, and the passing down of practical knowledge. The result is a construction culture rooted in place, marked by simplicity, durability, and a clear understanding of natural forces.

This article is not a nostalgic look at the past. Instead, it aims to explore how Portugal’s traditional building methods, from pre-Roman settlements to Islamic earthen architecture, continue to offer valuable lessons today. In a time of ecological urgency and architectural standardization, revisiting these techniques helps us understand how buildings can work with nature, not against it.

Pre-Roman Iberia: Community Structures and Building with the Land

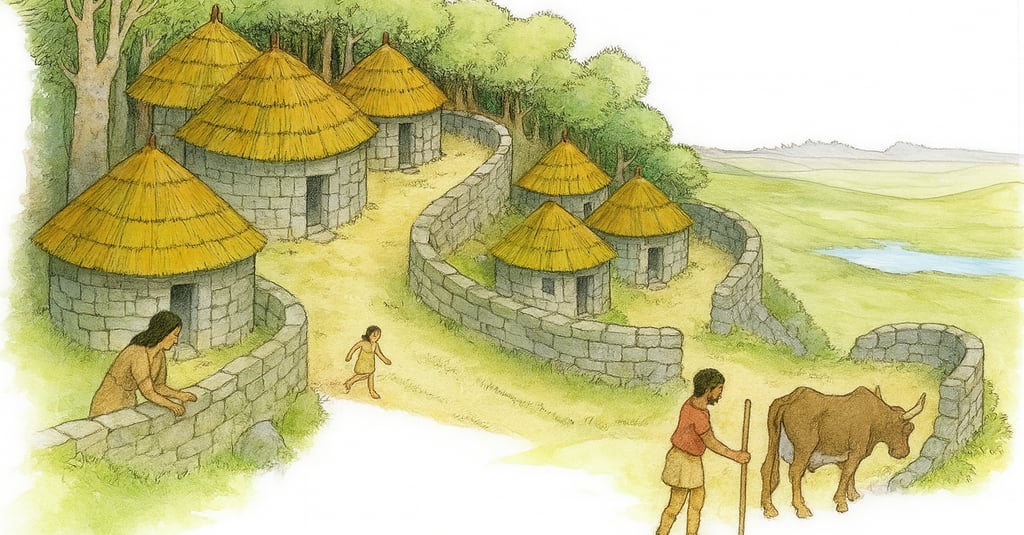

Before the arrival of the Romans, the Iberian Peninsula was home to a range of tribes and small settlements that developed their own architectural solutions in response to local terrain and weather. These early communities built with stone, clay, wood, and other materials readily available in their environment. The structures were often circular or elliptical and closely grouped, forming tight-knit village layouts known today as castros.

These were not isolated homes scattered across the landscape. They were part of a collective way of life, with houses built close together for both protection and social cohesion. In northern and central Portugal, castros were typically located on elevated ground and surrounded by walls made from stacked stone. Inside the walls, circular houses were built with stone bases and thatched or wooden roofs.

The choice of form was not just cultural but also practical. Circular buildings are structurally strong, require fewer materials than rectilinear ones, and offer good resistance to strong winds. The thick stone walls also provided insulation against both summer heat and winter cold.

The interiors were often modest, usually consisting of a single multifunctional space. Living, sleeping, cooking, and even animal sheltering could take place within the same volume. Floors were compacted earth, and hearths were central, offering warmth and light.

In regions where stone was less abundant, builders turned to mud, straw, and timber. In flatter areas, walls were sometimes made with a primitive form of adobe or packed earth. These materials were easily repairable, locally sourced, and thermally efficient.

Roman Influence: Engineering, Lime Mortar, and Organized Space

The Roman occupation of the Iberian Peninsula, which began in the 2nd century BCE, introduced a new architectural mindset based on engineering precision, standardization, and urban planning. While pre-Roman architecture was shaped by terrain and community, Roman construction brought axial organization, clearly defined public and private spaces, and a more formal approach to materials and technique.

One of the most significant Roman contributions was the widespread use of lime mortar. Unlike mud-based mortars or dry-stacked stone, lime allowed for greater structural cohesion and durability. Combined with baked bricks, concrete (opus caementicium), and stone masonry, it enabled the construction of arched doorways, barrel vaults, domes, and multistory buildings.

The Roman domus (urban house) and villae (rural estates) influenced Portuguese architecture for centuries. These buildings typically revolved around a central courtyard (atrium or peristyle), surrounded by porticoes and rooms that were carefully oriented to take advantage of sunlight and airflow. Shaded areas provided relief during hot summers, and the presence of impluviums (water basins) in the center of courtyards acted as natural coolers. The use of thermal baths and underfloor heating systems in wealthier homes also speaks to a refined understanding of environmental control.

In cities, Roman architecture introduced street grids, sewage systems, and public infrastructure such as aqueducts, forums, and amphitheaters. This logic of control and functionality extended to domestic spaces, with clearly zoned rooms: kitchens (culina), dining areas (triclinium), bedrooms (cubicula), and service spaces.

In rural areas, especially in the Alentejo, some Roman farms integrated with earlier Iberian construction methods. Foundations and wall cores were built with local stone and lime, while roofs used wooden beams covered in clay tiles.

What the Romans added to Portuguese building traditions was not just new materials and forms, but a sense of planning. Buildings were no longer just shelters but part of a broader social and technical system. While Roman architecture in Portugal eventually declined after the empire’s fall, its material logic and spatial clarity left a lasting imprint, particularly in regions where ruins were later reused and adapted by subsequent cultures.

Islamic Architecture in Portugal: Earth, Water, and Climate Response

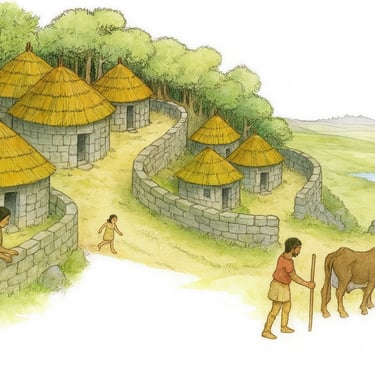

Between the 8th and 13th centuries, much of southern Portugal was under Islamic rule, particularly the Algarve and parts of the Alentejo. This period brought not only religious and cultural change but also a distinct architectural language that emphasized climate adaptation, resource efficiency, and a strong relationship between indoor and outdoor space.

The Islamic approach to building was grounded in pragmatism. In the hot, dry regions of the south, rammed earth (taipa) became the dominant building technique. It used compacted layers of moist soil inside wooden formworks, producing thick walls with excellent thermal inertia. Taipa was abundant, inexpensive, and easy to repair. It kept interiors cool during the day and released stored heat at night, offering a natural form of climate regulation.

Architectural forms also reflected this logic. Flat rooftops (açoteias) were commonly used for drying food, sleeping during hot nights, and collecting rainwater. Interior courtyards (riads) became the thermal and social heart of the home. Surrounded by shaded arcades and often including a fountain or garden, these spaces moderated temperature, improved air circulation, and offered privacy from the public street.

Islamic builders paid close attention to wind orientation, using narrow streets and strategically placed openings to direct air into buildings. Windows were often small and elevated, minimizing solar heat gain. Screens and latticework (mashrabiya) allowed for ventilation while maintaining privacy.

Water was more than a necessity. It was a cooling device, a source of sound and calm, and a symbolic reminder of paradise. The controlled use of water through fountains, cisterns, and irrigation channels turned even modest homes into environments of balance and comfort.

In Silves, which was once the capital of the Islamic kingdom of Al-Gharb, these influences are particularly strong. The city’s medieval layout, archaeological remains, and continuing cultural memory reflect a time when architecture was inseparable from both climate and ritual.

While much of this architectural legacy was gradually transformed after the Christian reconquest, many structural elements persisted. The use of earth as a building material, the importance of shaded patios, and the concept of passive climate control all continued to inform rural construction in the centuries that followed.

The Islamic period in Portuguese architectural history is not a chapter apart but a foundational layer. Its contributions remain visible in form, technique, and philosophy — prioritizing simplicity, function, and harmony with nature.

Christian Vernacular: Rural Architecture Rooted in Territory

After the Christian reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula, architecture in Portugal gradually absorbed and reinterpreted the techniques and forms left behind by Islamic builders. Rather than erasing this legacy, many rural communities adapted what already worked — especially in southern and interior regions — while introducing Christian symbols, religious buildings, and new construction patterns based on social and agricultural life.

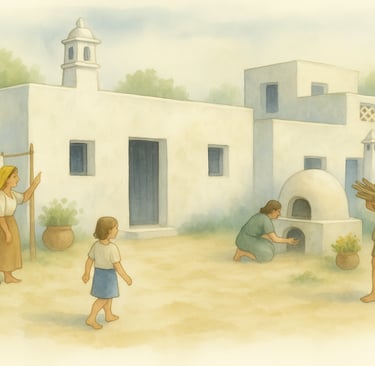

What emerged over time was a vernacular architecture that varied by region but shared common values: simplicity, durability, and a strong connection to the landscape. In contrast with urban centers, where Gothic and later Baroque styles gained ground, rural construction remained largely practical and anonymous, shaped more by custom and geography than by architectural fashion.

In the north, where granite is abundant, houses were built with thick stone walls, small windows, and steep pitched roofs designed to shed heavy rains and snow. Homes were often attached to animal shelters or grain storage, reflecting the close relationship between habitation and subsistence.

In the Alentejo and Algarve, the tradition of whitewashed lime-plastered walls became widespread. This finish not only protected the adobe or stone underneath, but also reflected sunlight, helping keep interiors cool. Roofs were flat or gently sloped, sometimes forming terraces accessible from inside. Chimneys, often elaborate and regionally distinct, became architectural symbols as well as functional elements.

Homes were typically small, with rooms arranged around a central space or hallway. In warmer regions, inner patios persisted as a common feature, offering shade and air circulation. Windows were few and small, placed strategically to control temperature and ensure privacy.

Construction methods continued to favor local materials. Adobe, schist, limestone, timber, and clay tiles were used in various combinations. Builders relied on manual labor and community effort, and repairs or expansions were carried out over generations.

This period also saw the development of agricultural outbuildings — cisterns, threshing floors, mills, barns — that were built using the same materials and techniques as houses. The result was a built environment that felt coherent, grounded, and deeply embedded in the rhythms of rural life.

Portuguese vernacular architecture during this time is notable for how it quietly integrated centuries of accumulated knowledge — including pre-Roman forms, Roman organization, and Islamic environmental logic — into a new language of construction that remained adaptable, resilient, and relevant.

Rammed Earth in Portugal: From Tradition to Continuity

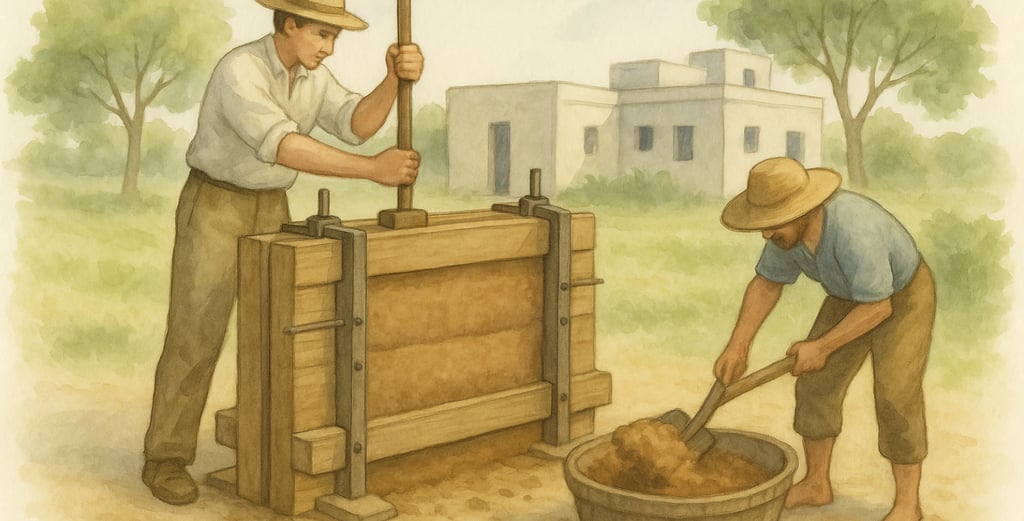

Among the most distinctive elements of Portugal’s traditional building methods is the continued use of rammed earth, known locally as taipa. This technique, which reached its height during the Islamic period, remained widely used across the southern half of the country well into the 20th century, particularly in the Algarve and Alentejo.

Taipa construction involves compacting damp earth in layers between wooden formworks. The earth may be stabilized with small amounts of lime or straw, depending on soil type and intended use. Once dry, the resulting walls are thick, strong, and provide excellent thermal insulation.

What makes taipa especially suited to the Portuguese south is its compatibility with the local climate and geology. The abundance of clay-rich soils, combined with long dry summers and mild winters, created ideal conditions for earth building. In areas like Silves, Loulé, and Ourique, entire villages were once built with taipa, and many buildings remain standing after centuries of use.

In addition to being a low-impact and locally sourced material, taipa walls offer significant environmental advantages. Their thermal mass regulates indoor temperatures, reducing the need for mechanical cooling or heating. The walls are breathable, helping to manage humidity levels, and they require minimal maintenance if well protected from prolonged moisture.

Over time, variations of the technique emerged:

Taipa de pilão: traditional rammed earth using wooden molds and manual compaction.

Taipa militar: more standardized and uniform, often used for military and civil works.

Taipa ensacada: a more recent innovation involving compacted earth inside fabric or geotextile bags, allowing for organic shapes, increased seismic resistance, and better moisture control.

The enduring presence of taipa construction is not just a technical matter, but a cultural one. It reflects a mindset that values sufficiency over excess, adaptation over uniformity, and respect for what the land offers.

Municipalities such as Silves have played a key role in preserving and promoting this heritage. In 1993, the city hosted the Meeting of Architects on Earth Construction in the Mediterranean, resulting in the publication of Construir em Terra no Mediterrâneo, a reference work that positioned Portugal within the wider Mediterranean tradition of earth building.

Today, taipa is experiencing a modest revival, not only as a heritage technique but as a response to contemporary concerns about carbon emissions, embodied energy, and resource scarcity. Builders, architects, and researchers are exploring ways to adapt and refine the method for modern use, while staying true to its original logic.

Taipa remains one of the clearest examples of how traditional Portuguese construction was never static. It evolved over time, adapting to changes in society and environment, yet always grounded in the materials and knowledge of place.

Continuing to evolve

The history of traditional Portuguese building is not a fixed style, but a process — one shaped by centuries of observation, adaptation, and respect for place. From the circular stone houses of the castro culture to the taipa walls of the south, each period left behind knowledge rooted in material honesty and environmental intelligence.

These construction methods were developed not through theory, but through need — using what was available, building for comfort, and adapting to the land rather than reshaping it. In a time when architecture often distances itself from its context, these traditions remind us that building well begins with understanding where we are.

Looking back at this legacy is not about revivalism. It is about learning how to move forward with greater care, using old knowledge to meet new challenges. The past has never been more relevant.

Get in contact

Innovating sustainable living through ecology and community.

© 2025. All rights reserved.

Newsletter

São Bartolomeu de Messines, Portugal